September 2018 Newsletter

Stephen Merritt, CPA, PC | Certified Public Accountants | (757) 420-5778

233 Business Park Drive, Suite 104, Virginia Beach, VA 23462

What’s Inside:

A grain of SALT in new IRS notice

Life insurance as the ultimate hedge

Funding your buy-sell with life insurance

Tax calendar

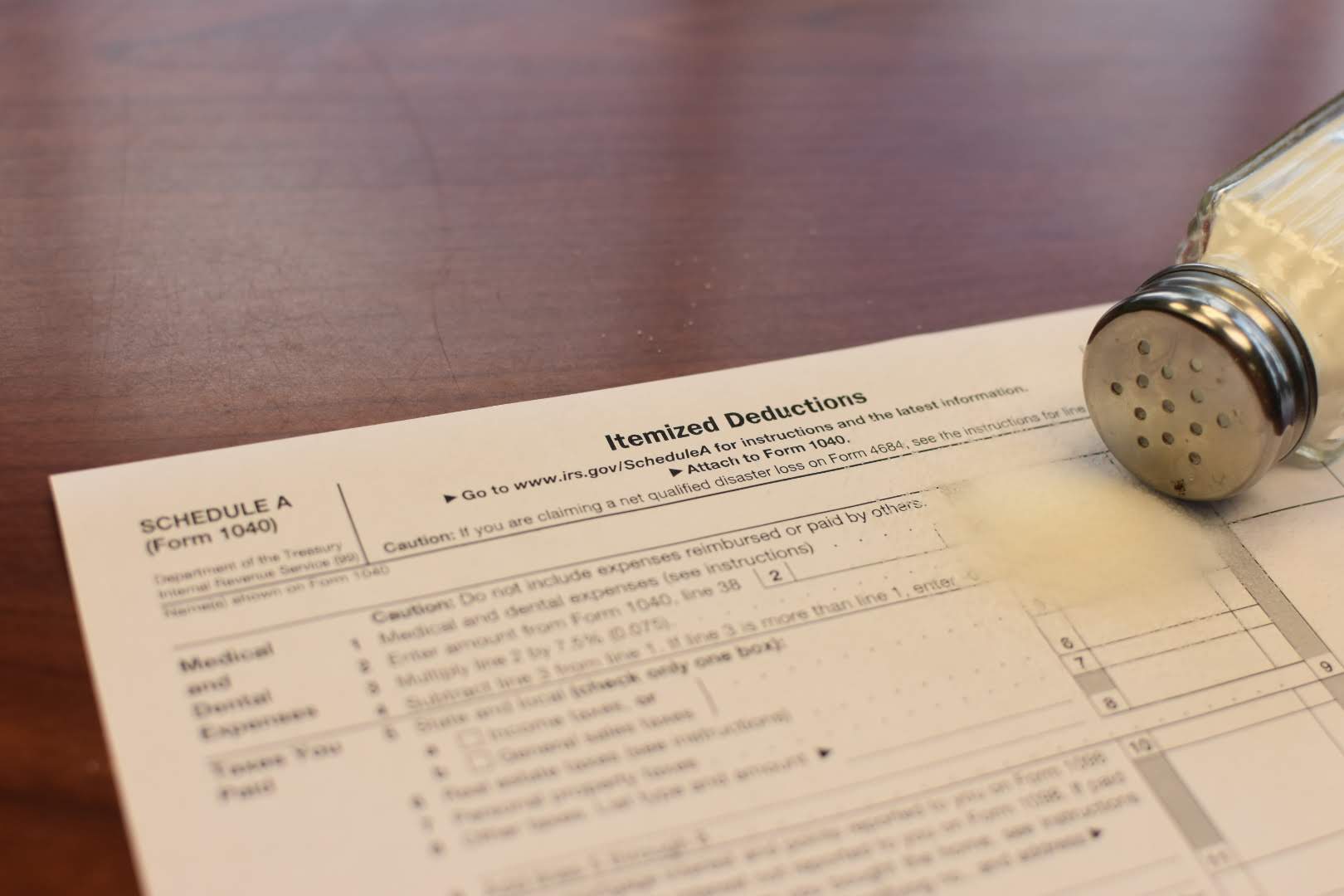

A grain of SALT in new IRS notice

Taxpayers who itemize deductions on Schedule A of their tax return have been able to deduct outlays for state and local income tax as well as property tax with no upper limit. (State and local sales tax may be deducted instead of income tax.) However, as of 2018, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 provides that no more than $10,000 of these state and local tax (SALT) expenses can be deducted on single or joint tax returns ($5,000 for married individuals filing separately).

Example: Marge Williams might have been able to deduct $20,000, $50,000, or even more in SALT payments in 2017. For 2018, Marge’s SALT deduction will be capped at $10,000. Thus, her SALT payments over $10,000 will be made with 100-cent dollars. Previously, those state and local tax bills might have effectively been paid with, say, 65-cent or even 60.4-cent dollars, depending on her federal tax bracket.

Political figures in high tax states worry that this sizable increase in net tax obligations will cause residents to flee to other states with lower taxes; moreover, residents of other states might be reluctant to move to places where taxes are steep. That may or may not be the case. After all, taxpayers subject to the alternative minimum tax have been making SALT payments with 100-cent dollars for years—SALT is an add-back item in the alternative minimum tax calculation, wiping out the tax benefit—so the new rule might not be as painful as it appears.

First responder

Nevertheless, high tax states are considering countermoves. The first state to act on this SALT pinch was New York, which enacted two-fold legislation in April. One aspect of this legislation is allowing New Yorkers to make contributions to designated health and education state charitable funds, which, theoretically, would qualify for federal and state charitable income tax deductions. Local governments are also authorized to create charitable funds.

Taxpayers making contributions to state charitable funds would also get state income tax credits, and taxpayers making contributions to a local charitable fund would get a property tax credit. The result could be reducing residents’ non-deductible SALT expenses while increasing deductible charitable donations.

The second part of the New York plan involves a voluntary payroll tax, paid by employers, starting at 1.5% and escalating to 5% in two years. This voluntary payroll tax also will generate state income tax credits. Apparently, the idea is that employers would offset the extra expense by cutting wages, which will wind up as a wash for employees because of the tax savings.

IRS takes notice

Observers wondered what the IRS would think about such “work arounds” of the new SALT limits. Their questions were answered swiftly in IRS Notice 2018-54, released in May. The IRS characterized such state efforts as attempts to “circumvent” the new law. Federal tax deductions are controlled by federal law, the notice pointed out: Just because a state says that certain outlays are deductible on federal tax returns does not necessarily make it the last word on the subject.

In the notice, the IRS announced that it will publish proposed regulations on this issue. The agency mentioned “substance over form,” indicating that challenges are likely. Officials in New York and other high tax states reportedly will continue to seek SALT relief. Tax preparers and taxpayers may want to carefully consider whether they want to be among the proverbial dogs in this fight.

Trusted advice: Deducting tax payments

The IRS lists the following types of deductible nonbusiness taxes:

· State, local, and foreign income taxes

· State and local general sales taxes

· State, local, and foreign real estate taxes

· State and local personal property taxes

Taxpayers can elect to deduct state and local sales tax instead of state and local income tax, but not both. Those who elect to deduct state and local sales tax may use either actual expenses or optional IRS sales tax tables.

Life insurance as the ultimate hedge

Many people think of life insurance as a product for family protection. The life of one or two breadwinners is insured; in case of an untimely death, the insurance payout can help with raising children and maintaining the current lifestyle.

Once the children are able to live independently and a surviving spouse is financially secure, insurance coverage may be dropped. Such a strategy uses life insurance as a hedge against the risk of lost income when that cash flow is vital.

This type of planning is often necessary. That said, life insurance may serve other purposes, including some that are not readily apparent.

Final expenses

When someone dies, funeral and burial expenses can be daunting. In addition, the decedent’s debts might need to be paid off, perhaps including substantial end-of-life medical bills. Many insurers offer policies specifically for these and other post-death obligations, with death benefits commonly ranging from $10,000 to $50,000.

The beneficiary, typically a surviving spouse or child, can receive a cash inflow in a relatively short time. Generally, this payout won’t be subject to income tax. The result might be less stress for beneficiaries during a difficult time and a reduced need to make immediate financial decisions in order to raise funds.

Investment support

This year’s stock market volatility has worried some investors, who may be tempted to turn to safer holdings, which have little or no long-term growth potential. Prudent use of life insurance might help to allay such fears.

Example 1: Jill Miller has $600,000 in her investment portfolio, where she has a sizable allocation to stocks. She is concerned that an economic downturn could drop her portfolio value to $500,000, $400,000, or less. Therefore, Jill buys a $250,000 policy on her life.

Now Jill knows that her children, the policy beneficiaries, will receive that $250,000 at her death, income-tax-free, in addition to any other assets she’ll pass down. This gives her the confidence to continue holding stocks, which might deliver substantial gains for Jill and her children.

Balancing acts

Life insurance also can help to treat heirs equally, if that is someone’s intention, but circumstances create challenges.

Example 2: Charles Phillips, a widower, owns a successful business in which his older daughter Diane has become a key executive. Charles would like to leave the company to Diane, but that would exclude his younger daughter Eve, who has other interests.

Therefore, Charles buys a large insurance policy on his life, payable to Eve. This assured death benefit for Eve will help Charles structure his estate plan so that both of his daughters will be treated fairly. There is a potential downside to consider if Charles is wealthy enough to have an estate that is subject to the federal estate tax ($11.18 million in 2018). In this case, a large insurance policy will swell his gross estate, leading to a greater estate tax liability.

Life insurance may be especially helpful when one or both spouses has children from a previous marriage.

Example 3: Jim Devlin’s estate plan calls for most of his assets to be left in trust for his second wife, Robin. At Robin’s death, the trust assets will pass to Jim’s children from his first marriage. Robin is younger than Jim, so it could be many years before his children receive a meaningful inheritance.

Again, life insurance can provide an answer. If Jim insures his life and names his children as beneficiaries, his children may get an ample amount without having a long wait.

Proceed carefully

The life insurance marketplace ranges from straightforward term policies to so-called permanent policies (forms of variable, universal, or whole life) that have investment accounts with cash value. In some cases, policyholders can tap the cash value for tax-free funds while they’re alive. Our office can help explain the tax aspects of a policy you’re considering, but you should exercise caution when evaluating any possible purchase of life insurance. Find out what you’ll be paying and what you’ll be receiving in return.

Funding your buy-sell with life insurance

Among the trigger events of a small company buy-sell agreement, death of a co-owner typically is included.

Example 1: Wendy Young and Victor Thomas both own 50% of YT Corp. They have a buy-sell, which calls for Wendy to buy Victor’s interest in YT if he dies. Similarly, Victor will buy Wendy’s interest in YT from her estate if she is the first to die.

Small company buy-sells such as the one for YT Corp. often fall into one of two categories:

- Cross purchase. Wendy will buy Victor’s shares directly from his heirs, or vice versa.

- Redemption. Here, YT Corp. will buy the decedent’s interest. If Victor is first to die, YT will buy his shares, leaving Wendy as the sole owner.

Finding the funds

With either type of buy-sell, a “buy” must be made, and the decedent’s interest in the company might be extremely valuable. Therefore, life insurance often is used to provide the funds for the buyout.

Example 2: In a cross-purchase arrangement, Wendy will acquire a policy on Victor’s life, and Victor will own a policy on Wendy’s life. If Victor dies, the insurance payout will go to Wendy, generally free of income tax. Wendy can use this money to buy Victor’s interest in YT Corp. from his estate at the price set in the buy-sell.

If Victor is the survivor, the process will take place in reverse.

Pros and cons

There are some advantages to a cross-purchase arrangement. If the shares have appreciated over the years, Wendy will get a basis step-up to current value when she buys Victor’s shares. That could reduce the tax on a future sale of all of Wendy’s shares.

On the other hand, the premiums on a large life insurance policy could be substantial. Wendy and Victor might not be willing and able to pay these costs personally. This issue could be further complicated if, say, Victor is much older than Wendy and in poor health. The premiums on a

policy insuring Victor could be much higher than the premiums for a policy insuring Wendy; this disparity may have to be resolved by some financial arrangement between the owners.

In addition, not every small company has 2 co-owners. With 3 owners, each would have to own life insurance policies on 2 others, for a total of 6 policies. Four owners would need 12 policies, and so on.

Regarding redemptions

Some of these cross-purchase problems can be resolved by using a corporate redemption plan.

Example 3: In a redemption plan, YT Corp. needs to buy only two life insurance policies: one on Wendy and the other on Victor. If Victor dies, the death benefit goes to YT, which uses the money to redeem Victor’s shares. If Wendy dies first, YT will buy her shares.

This method addresses the problems of multiple owners, uneven premium payments, and personal outlays for premiums. On the negative side, a redemption plan places what might be valuable insurance policies in the company’s possession, subject to creditors’ claims. Adverse tax issues also may arise, including the loss of a basis step-up for the surviving co-owner or owners.

Other ways to use life insurance for buy-sells may be suggested by an experienced insurance agent. For instance, a trust might be created and funded by multiple co-owners, with an independent trustee acquiring life insurance policies on those owners’ lives. The taxation of a trusteed buy-sell might be more favorable than taxation of a redemption plan. Our office can explain the likely tax consequences of any strategy you’re considering for funding a buy-sell through life insurance.

If your company initiates a buy-sell to be funded with life insurance, make sure to keep the policies up to date. If the company’s value grows but the coverage doesn’t increase, the insurance payout could be only a fraction of the required purchase price.

Tax Calendar

SEPTEMBER 2018

September 17

Individuals. If you are not paying your 2018 income tax through withholding (or will not pay in enough tax during the year that way), pay the third installment of your 2018 estimated tax. Use Form 1040-ES.

Employers. For Social Security, Medicare, withheld income tax, and nonpayroll withholding, deposit the tax for payments in August if the monthly rule applies.

Corporations. Deposit the third installment of estimated income tax for 2018. Use the worksheet Form 1120-W to help estimate tax for the year.

Partnerships. File a 2017 calendar-year return (Form 1065). This due date applies only if you timely requested an automatic 6-month extension. Provide each partner with a copy of their final or amended Schedule K-1 (Form 1065) or substitute Schedule K-1.

S corporations. File a 2017 calendar-year income tax return (Form 1120S) and pay any tax, interest, and penalties due. This due date applies only if you timely requested an automatic 6-month extension. Provide each shareholder with a copy of Schedule K-1 (Form 1120S) or a substitute Schedule K-1.

OCTOBER 2018

October 15

Individuals. If you have an automatic six-month extension to file your income tax return for 2017, file Form 1040, 1040A, or 1040EZ and pay any tax, interest, or penalties due.

Employers. For Social Security, Medicare, withheld income tax, and nonpayroll withholding, deposit the tax for payments in September if the monthly rule applies.

Corporations. File a 2017 calendar-year income tax return (Form 1120) and pay any tax, interest, and penalties due. This due date applies only if you timely requested an automatic 6-month extension.

October 31

Employers. For Social Security, Medicare, and withheld income tax, file Form 941 for the third quarter of 2018. Deposit any undeposited tax. (If your tax liability is less than $2,500, you can pay it in full with a timely filed return.) If you deposited the tax for the quarter in full and on time, you have until November 13 to file the return.

For federal unemployment tax, deposit the tax owed through September if more than $500.